For most of my life, I have struggled with negative self-talk. I don’t remember when it started, but by the time I got to middle school, I told myself on the regular that I was a failure, that no one liked me and no one ever would, and so on. As an adult, that’s led to imposter’s syndrome as well as me consistently devaluing my own successes and accomplishments as soon as they happen. If I complete a project or get a big promotion, I’ll instantly tell myself it doesn’t count or that it doesn’t matter. Every year, I dread my birthday and New Year’s, seeing both as opportunities to examine all of the things I haven’t yet achieved and how much time I’ve “wasted.”

Intellectually, I know that this is wrong. I’ve written articles I love, helped other writers grow, and even recorded a solo full-length album while working a full-time writing job back in 2017-18. These days, I host two podcasts per week on top of a full-time editing job. I’m in a happy long-term relationship with a fascinating, beautiful woman. I have some seriously awesome best friends and a solid circle of acquaintances. The list goes on.

Yet, even with all of that, I was still beating myself a lot -- until recently. I’ve changed a lot about my self-care routine this past year, and it’s been a huge help, but this blog post isn’t going to be about how regular bedtimes and a different drug cocktail have helped me turn my life around -- although that stuff has certainly been useful, and I’m lucky to have the resources to make those changes. This blog post is actually going to be about the One Weird Trick that my psychiatrist told me about in our most recent appointment. It’s made a huge difference for me in terms of how I approach negative self-talk, so I’d like to pass it on for the benefit of people who might need it as much as I did.

My psychiatrist’s tip actually reminded me of one of my favorite posts on the internet, “Why Procrastinators Procrastinate.” It’s an old article and it certainly has its issues (it opens with a bizarre take on “obese people” and “overeating,” for example), but its larger framework has stuck with me. In addition to struggling with self-hatred, I also struggle periodically with procrastination, and in my experience, both of these bad habits allow each other to multiply endlessly. I’ll procrastinate something for a bit, then barrage myself with negative self-talk about how I didn’t get it done sooner, which will make me even less motivated to dive in because I’ll be feeling bad about my abilities, and so on. The article I linked acknowledges that aspect of procrastination and does so in a funny and relatable way.

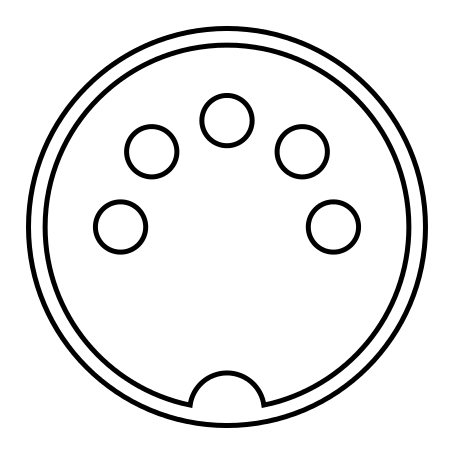

The most interesting part of the article is its evocative description of the difference between the people who don’t suffer from chronic procrastination, and the people who do. The person who doesn’t procrastinate is depicted as a “rational decision-maker” at the helm of a ship’s wheel inside of a human brain, directing it forward on a steady, well-planned course. Then there’s the chronic procrastinator, who actually has the same exact “rational decision-maker” at the helm in their brain -- except there’s also a sneaky little monkey in the room, bouncing around, tempting the decision-maker with all manner of distractions and indulgences and excuses to stop working.

For a long time, I viewed this framework as both a humorous and useful way to think about my worst impulses. I saw those impulses as being outside of myself, like some pesky little animal who kept on bugging me and waylaying my best interests. But this wasn’t actually a useful framework to get me to stop procrastinating, nor did it stop me from insulting myself over it. Although the original article has a follow-up with some tips on how to stop procrastinating (such as, break your big-picture tasks down into manageable steps), I never found it to be particularly illuminating. When I got stuck in a bad cycle, I’d find that I couldn’t start any task, no matter how small, because I was so busy inwardly yelling at myself. Well, both at myself and at my procrastination monkey.

It turns out that yelling doesn’t work. But I wasn’t sure what I should do instead.

I described this ongoing problem to my psychiatrist, who gave me the tip that’s changed my entire approach to negative self-talk. He invited me to view myself as both an adult and a child. My child self is still a part of me, still a fundamental aspect of my personality. She’s smart and curious, and she loves to “play pretend” or to hole herself up in the attic to read fantasy novels for hours on end. Then there’s my adult self. She’s smart and curious, too, but she’s also better at long-term planning and prioritizing what matters. She’s had enough life experiences, both good and bad, to see the big picture clearly. Except she’s got to put up with child me, who’s still a part of me and hanging around all the time -- and she doesn’t want to do any work. She hates school and authority and any type of ruleset that she perceives as being unfair or pointless. She just wants to have fun!

child me

age 13, or thereabouts, sitting on the edge of an armchair

You’ve probably already noticed the key difference between this framework and the previous one. Instead of dealing with an obnoxious monkey -- an uncontrollable, wild animal wreaking havoc on my innocent brain -- I’m dealing with a young child. And it’s a child for whom I have a lot of affection. I remember how unhappy and unfulfilled I felt back then, as well as the extent of my curiosity and creativity -- the admirable qualities that made me into the adult I am today. I can’t blame my inner child for wanting to log off work and get in some playtime. Honestly, she makes some damn good points. Sometimes she bugs me, but even when that happens, I have to admit she’s making a decent case.

That’s why I always endeavor to respect her. Instead of the monkey that I had insulted and derided -- by extension, insulting myself -- I now approach my inner child with the care and love of a cool babysitter. My psychiatrist put it this way: if you were going to convince a child to stop playing Super Smash Brothers and do their homework, would you insult them? Would you hurt them? I sure hope the answer is “no,” because those techniques wouldn’t work at all. They would traumatize your child, and also, their homework wouldn’t get done. Okay, maybe the work would get done -- but at what cost, especially in the long term? Positive reinforcement has been shown to work a hell of a lot better, no matter how old you are.

I haven’t completely beaten procrastination or negative self-talk. There are some more tips that my psychiatrist has given me that I’ve been trying, such as immediately rewarding myself with self-praise whenever I start a task (it feels corny, but it does help). More importantly, though, I’m spending a lot less time insulting myself. I’ve realized that a lot of the impulses about myself that I find annoying are actually reflections of my own inner child, and that’s a side of myself that I value a lot. In other words, these aren’t my “worst impulses” at all, or bad habits that I need to stamp out. They’re just a reflection of the childlike passion and sense of joy that I wish I still had -- and, hey, turns out I do still have it. It’s been inside me all along. I want to cherish that and encourage that, not squelch it with constant haranguing about the importance of getting all of my chores done.

My brain will always be a work in progress. But at least I’ve found a way to hate myself slightly less, lately. I hope it helps you, too, whoever you are.